What is the mysterious appeal of lace? What makes lace so special among fabrics?

My current writing project, a cozy mystery sequel to Alibis and Aspidistras, centers on an incident at the Lacemakers’ Ball–an annual event in the fictional town of Grey Harbor. So, not surprisingly, I’ve been thinking a lot about lace. And how to create an air of mystery.

Lace itself has an air of mystery. On the one hand, it’s a fabric (or a trim). On the other hand, it depends as much on air and empty space as it does on substance. It teases, blocking your view, but only partially. It occurs to me that the appeal of lace is a bit like the appeal of reflections and shadows. Lace shows you not just itself, but a bit of something beyond.

Lace is mysterious in another way. How does that delicate network hold together?

There are different kinds of lace, of course. I understand crochet lace–how you can take one very long thread and make loops within loops to create a structure than doesn’t simply unravel. And years ago I took an introduction to bobbin lace and learned the basics of how threads and pins used together could create a woven web that remained even after the pins were removed–and how that web could be created in many varied patterns. But even having seen it firsthand, I find it amazing that it doesn’t just fall apart.

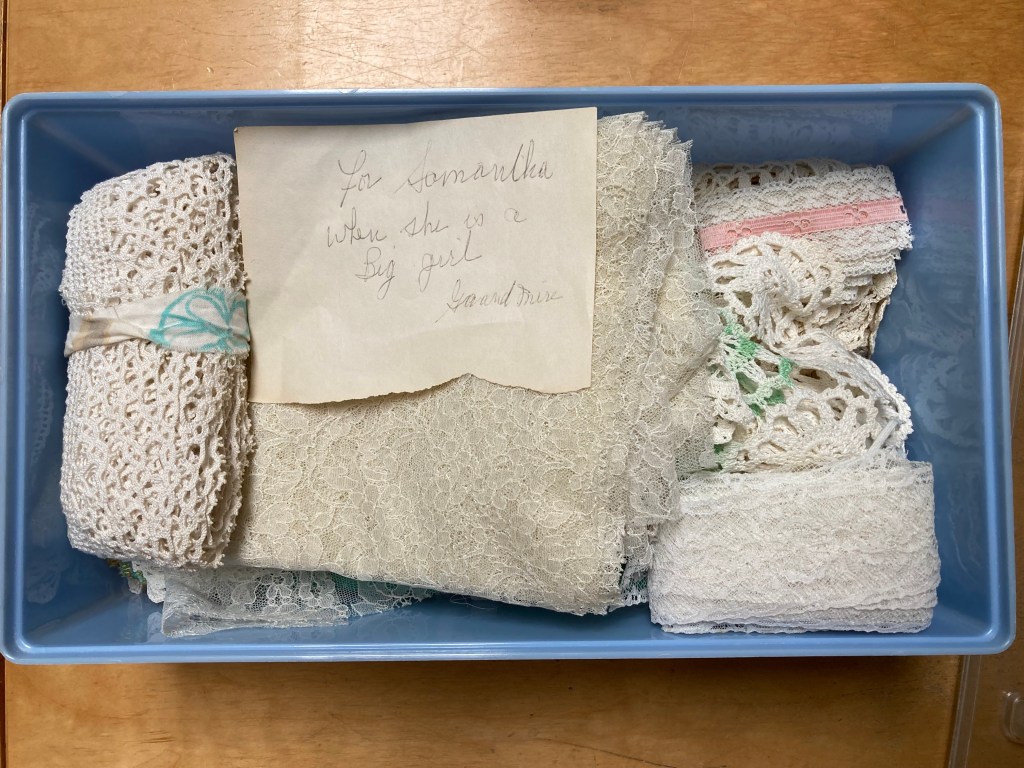

This brings me to more personal mystery involving lace. My grandmere–my paternal grandmother–left me a box of lace. She had it stored away in a plastic box with a flower-embossed lid and a note, “For Samantha when she is a big girl.” I loved frills and froufrou as a little girl, so she probably imagined me adding lace trim to my clothes and household linens, just as she filled her house with lacy runners and ribbon-trimmed drapes.

Where did the lace come from? Were these all bits and pieces left over from her own projects? My grandparents were thrifty and she would have saved any remnants, and probably anything that could be salvaged from old clothes as well. Or perhaps some of it was for projects she never started?

On the other hand, one of the pieces in the box was a runner made of crocheted doilies, very like the partially completed doilies that were in with her other things, so presumably that piece is one she crocheted herself. Looking at it, I realize that I know very little about my grandmere’s skills beyond cooking and sewing. She once demonstrated tatting to me, but I wasn’t especially interested at the time and never asked to see more. Somewhere I have a wisp of tatting in the same beige thread as the partial doily–what else did she create? And did her lacemaking ever extend beyond crochet and tatting?

Some of the lace is clearly machine-made, and probably the rest of it–other than the doilies–is too. But I wish now that I had asked her to tell me more about her skills, instead of taking for granted the things that she made us–the crocheted cushion covers, and the pillows with our initials embroidered on them. It’s too late now. It will forever remain a mystery.

Till next post.